- How to Adjust X and Y Axis Scale in Arduino Serial Plotter (No Extra Software Needed)Posted 5 months ago

- Elettronici Entusiasti: Inspiring Makers at Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 5 months ago

- makeITcircular 2024 content launched – Part of Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 7 months ago

- Application For Maker Faire Rome 2024: Deadline June 20thPosted 9 months ago

- Building a 3D Digital Clock with ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- Creating a controller for Minecraft with realistic body movements using ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- Snowflake with ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- Holographic Christmas TreePosted 1 year ago

- Segstick: Build Your Own Self-Balancing Vehicle in Just 2 Days with ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- ZSWatch: An Open-Source Smartwatch Project Based on the Zephyr Operating SystemPosted 1 year ago

Interview to Alastair Parvin and Wikihouse project

For the latest episode of our Meet The Founders interviews we are releasing today the intervivew we made recently with WIkihouse funder Alastair Parvin. The interview come up superbe and it touches a lot of topics, ranging from furniture manufacturing to VC strategies, from crowdfunding to openness.

For the latest episode of our Meet The Founders interviews we are releasing today the intervivew we made recently with WIkihouse funder Alastair Parvin. The interview come up superbe and it touches a lot of topics, ranging from furniture manufacturing to VC strategies, from crowdfunding to openness.

There are the kind of post you cannot miss on OpenElectronics: terrific vision, a committed founder immersed in a great context of innovation (partners, friends, UK seems a real hub for radical innovation these days).

As Alastair told us WikiHouse wasn’t only created by him alone but, like many interesting projects, its genesis and authorship is plural and fuzzy so we asked him about the genesis of the project and his background in doing this, in details:

[Alastair Parvin] It’s important to bust that myth of the solitary architect! I think probably everyone involved in WikiHouse has come at it from their own particular approach, but with a common awareness that housing is a problem worth looking at, and that Open Source and distributed manufacturing have the potential to be disruptive in the way we make it. Although I’ve been fascinated by OS movement since I was a student (I remember my friend Adam introducing me The Cathedral & the Bazaar by Eric S Raymond when we were undergrads), my personal approach to WikiHouse is through the economics of housing production. Firstly realising that most of the housing architects were working on were not actually commissioned as places to live, but as real-estate assets, and asking why it was that even in relatively wealthy countries, relatively wealthy people live in some kind of housing crisis, whether that’s a crisis of affordability, a crisis of debt, a crisis of sustainability or a crisis of quality. Before we began working on WikiHouse I began an ongoing piece of research called ‘A Right to Build’, which was looking at exactly these issues, and looking for new ways to scale user & citizen-led development as a mass-housebuilding industry; one which is fundamentally more focused on all the things we (and our governments) say we look for in housing: quality, affordability, flexibility, energy performance, sociability, resilience, which speculative developers see (quite rationally) as costs.

[OpenElectronics] Is Wikihouse a demonstrative project or you really want to build a marketable alternative?

In this case, are you already aware if this is going to be cheaper or more functional with respect to traditional building techniques.

[Alastair Parvin] Yes, of course. We wouldn’t be interested in it if we didn’t think it had substantive potential to be disruptive. Of course it began as – just that – an experiment, a concept, and it’s slowly working through prototype towards becoming a reality. Fundamentally, WikiHouse will only be disruptive inasmuch as it is able to lower practical thresholds of times, cost, difficulty and carbon in getting access to better quality housing. But that equation isn’t straightforward for three reasons. First, because the cost of getting access to CNC machines, which is coming down, but still has an associated cost, and second, because of the cost of materials. So we know that WikiHouses are rapid to build, fairly easy to build, and we’re pretty confident about the performance of them. In areas where cost of Labour outweighs cost of materials (US, UK, Europe etc) then we’re pretty sure WikiHouse is going to be very affordable, because it enables you to do the work for yourself (to invest “sweat-equity” – but with less sweat!). We’re currently working on the first full, lived-in house types and that looks like it’s coming in somewhere near £600/m2. That’s an estimate. Hopefully we can keep working that down.

The third big thing of course is about getting access to land, which is part of the broader ‘Right to Build’ project. Our ambition is to use WikiHouse as a platform to design new development models which, again, make it much easier for landowners to consider releasing land for legitimate user (citizen) -led neighbourhood development models.

[OpenElectronics] Are you experimenting with new materials other than Plywood and with other constructive challenges such as energy, insulation, water harvesting, etc..? Is the community active on this topic?

[Alastair Parvin] Yes. Of course the end destination of WikiHouse should be to use the same set of design principles to develop a range of technologies, from earth construction etc. We’re only working with Plywood now because it’s a disruption we can make now (you’ve got to start somewhere). The next step will be to look at sheet materials using (for example) reprocessed plastics. We’re connecting with, and there are lots of people in the WikiHouse community interested in all kinds of technologies, economies, locations and problems, and hopefully increasingly connecting up with other open projects developing, for example open off-grid energy products etc. One product we’re working on is high-energy windows (which might seem mundane but might actually be more useful than houses!). It’s a big open challenge, so if someone is working on those things, or looking for a project, there’s huge potential in starting an open project to develop those things. That said, the capacity of the WikiHouse platform to support that sharing and collaboration is hugely limited at present. (We use google groups, which is a bit like collaborating in the 1990s! Others are using facebook, whilst some, quite understandably, feel uncomfortable about doing that). We’re currently trying to get some funding to build a much more open, accessible wiki, which can practically work to support 3D hardware. This is something which, for example, Open Tech Forever are doing awesome work on.

[OpenElectronics] What kind of reception among the construction industry? Did you try to confront with them?

[Alastair Parvin] Generally it really doesn’t need to be that confrontational. Sure, I think most of the construction industry will broadly ignore it, but others have been incredibly open and interested in working on projects. Almost everyone in construction knows there’s a need for innovation! There’s a general myth that developers are the ‘bad guys’; to quite self-build expert Stephen Hill “We need to stop beating them around the head for not doing something they’re not designed to do, and find someone who is”.

[OpenElectronics] What kind of funding is actually making possible for you to work on Wikihouse project?

[OpenElectronics] What kind of funding is actually making possible for you to work on Wikihouse project?

[Alastair Parvin] Obviously the large majority so far has been volunteered time by ourselves and others, and investment by our studio, 00 (‘zero zero’) and the engineers we work with, Momentum. To start with, exhibitions and events essentially paid for prototypes, and as the system gets more advanced, and we’re now working on the first full houses, those micro-commissions are helping to drive development. Every team has a different funding model, you can ask the same question of WikiHouseNZ for example and probably get a different answer!). There has also been a small amount of crowdfunding, which is slow but fantastic. We are also in the process of seeking some seed funding to help support the platform as a whole

[OpenElectronics] Can you tell us the reason behind the Crowdfunding Campaign and the three objectives you choose? Is it really the way to go for initiatives that, like yours, want to build in the commons?

[Alastair Parvin] It’s not so much that there are three objectives, but that there are three development streams, and a list of development goals / milestones along that journey. The reason is probably self-evident, but I’m not sure if we’d say that it’s the right or wrong way to do anything. As I said, most funding actually is project-by-project. A few months ago we published the WikiHouse constitution which shows how funding works in the community, and on the long-run our ambition is to lead development, but ultimately position ourselves as just one of many WikiHouse teams (of which there are an ever-increasing number!) and for the platform to host open access community tools for WIkiHouse projects / goals to seek funding. We’re really just doing what we can, when we can, testing what works, and slowly trying to get the project out of our inboxes. We don’t know the correct answers yet, and of course there’s a big gap between our ideal platform and our immediate resources (to put it lightly!)

[OpenElectronics] Isn’it it risky for you to rely that much on a non open source software like Sketchup?

[OpenElectronics] Isn’it it risky for you to rely that much on a non open source software like Sketchup?

[Alastair Parvin] There’ll always be a range of views on this, from the hardcore purists on one end who say you shouldn’t use anything that isn’t open, to those on the other who might too-easily compromise the legitimacy and openness of their project by being bounded to a commercial interest. It’s a really important issue. To be honest, the first is a kind of myth anyway, because you’re probably using a laptop which isn’t open source, eating food that isn’t open source and so on. We can’t rewrite the whole world at once, and I think it would be foolish to not start doing something because you can’t find the open tool to do it with, we’d never make any progress. At the same time, when it comes to, for example, Sketchup, we just used it because it was there, it’s easy to use and share stuff with, and you could write open plugins for it, but we’re very careful that we’re not bound to SketchUp, we’re just using it. There’s no conflict of interest. If there’s a better, easier to use tool that’s open and easy to use as a standard, we’ll start using that. These guys in NZ have made an awesome piece of software called Spoke Creator which might allow us to do in-browser parametric design, to initially generate 3D models based on simple inputs like height, length, layout etc. This is one of the big open challenges at the moment, so if any grasshopper-gurus are interested in working on it, please do! Likewise, if anyone knows of any really good, easy to use open software equivalents, and thinks they can make WikiHouse work in them, that would be interesting.

There’s a broader question behind that, which is: What do we actually mean by’ Open’? Obviously Michel Bauwens is super-articulate on this. For us there are four key aspects to it. First, open as in Open Access to shared commons. Second, open as in radically transparent and accountable. Third, open, as in open participation: open governance, which includes things like organisation structure, ownership, trademarks etc. But there’s also a fourth aspect of open, which I think often gets overlooked, because it is also practiced by ‘closed’ organisations, which is the openness that comes from designing-down thresholds of time, cost, skill, carbon, and cultural barriers. Arguably that’s the most immediately disruptive part of open, and has been behind some of the major industrial revolutions (Obvious example: the printing press) but it ultimately is most valuable if backed by the other forms of openness. It’s of limited use publishing something under open license if it’s hidden in a complex 1000-word document or, in our case, reams and reams of messy online forums. We need to design simple, accessible interfaces, products and protocols.

This is key also when talking about collaboration. We all love to proclaim collaboration as an idea, but there’s also a paradox there, which is that some of the most powerful and effective forms of mass-collaboration have actually been ones where the least possible interaction is strictly necessary between collaborators. i.e In the case of a chunk of code, you can often just download it and use it, you don’t need to email anyone. That’s perhaps an uncomfortable reality.

[OpenElectronics] Have you ever been approached by traditional Venture Capital firms? If yes, was the open source approach somehow problematic for them?

[Alastair Parvin] We started out with the assumption that we couldn’t go to the dragons with this.. by definition! That certainly makes life much slower, but it’s also necessary and… wonderful in its way. Like a lot of people now, we spend a lot of time thinking about open ventures, and what open commercial operation might look like. In general terms, my impression is that everybody is quite enthusiastic about the idea that you can open up all your I.P and also still make money selling goods and services over and above the raw I.P; the only people who are nervous are the investors and VCs. I suspect that’s almost out of habit, because why take a risk in that early stage of an enterprise? If more open projects succeed, perhaps this will change. The most likely compromise might be enterprises keeping their IP closed for the first 6-12 months but then being allowed to release open I.P after that. But ultimately you’d hope investors will be able to invest in open ventures who release early, release often and have open governance.

[OpenElectronics] Where’s the difficulty, if any, that you encountered since building open-source knowledge, with no focus on IP? Is people skeptical about that?

[Alastair Parvin] This is a hard question. There are of course, a huge variety of small technical difficulties that can be frustrating and enjoyable to overcome, such as dealing with variance and expansion in plywood in weather conditions, different CNC machines etc. Solving these are of course, are what the project is about; the path of slow progress! Likewise there are obvious limitations to our progress so far (eg We’ve only developed a system for places where there is affordable access to plywood), but again, we know that it’s a step-by-step iterative project with no defined destination, just a continuous direction of travel.

Generally, the things that people are sometimes sceptical about are not actually the hardest problems, ie things we’re confident we can prove. The really great challenges in doing an open project actually are: First, resourcing our own time. As it’s often said “Open=/Free”. So it’s taken us a long time just to be able to do this for a frustratingly small team. The second is the frustration of not being able to support and connect with the community, again, because we don’t have the time. At any give point, you always need a better platform to get collaboration out of our inboxes, and you’re split between hundreds of emails and actually trying to work on the project. People have been wonderfully patient with our time-scarcity, as we’ve spent the last year or so running around like nutters, not sleeping, and being slow to reply to emails…. or to respond to interview questions, in your case (sorry!). You really have to learn how to focus, but we hate the idea of being rude or letting people down.

[OpenElectronics] Is there a specific use case you see for Wikihouse (eg: developing countries, pop-up post crisis housing, rural housing, …)

[Alastair Parvin] One of our design principles is ‘Design for your own locality / economy, then share’. So we’ve started with affordable housing in West, but the ultimate vision should be to support a range of open vernaculars for different climates and economies, shared in commons. The interesting thing about housing crisis is that we experience the same crisis in different ways. In the West, its a crisis of debt, affordability, sustainability, sociability and quality; so there’s a strong case for shifting from financial-capital led top-down housing to user and citizen led housing which combines both financial and social capital. In the emerging economies that crisis is experienced as slum housing. In those areas, the immediate need is often not shelter but infrastructure. So there’s an equally strong case in finding development models that allow municipalities to see user / small-maker made housing as potentially safe, healthy, secure etc.

When people see WikiHouse, sometimes they say ‘this would be good for disaster relief’, but actually I always say that’s probably the one time you don’t want WikiHouse, you just want to get your head down, survive and mourn. Internationally, UN and aid agencies are actually pretty good at disaster relief housing, the problem is that often six months to a year down the line, people are still living in emergency housing; the cranes, the concrete and the financial capital don’t come, or when they do, they often exclude the original communities. So actually what’s needed are technologies and tools (eg a community factory / university) that allow those communities to invest social capital into making their own houses and neighbourhoods and have the resilience to grow them, maintain them and establish micro-economies there. That for example, is broadly what the WikiHouseNZ team are trying to do post earthquake in Christchurch. So it’s not so much about ‘no economy’ as ‘low economy’, which may be less dramatic, but is arguably a bigger need.

[OpenElectronics] What’s the long term goal of Wikihouse project? What plans do you have to put this in practice?

[Alastair Parvin] The best thing I can probably do is refer you to the published wikihouse development goals / milestones doc on our website. A global construction commons, with open design, planning tools and low-cost, high-performance hardware solutions to housing, infrastructure etc. Our goal is to get both that platform, those tools and that hardware to a point where it can be scaled, it can support an open micro economy, and have sustainable revenue to support the host platform. As I said previously, there’s no defined ‘end’ point to that, just an event-horizon for continuing growth, and all we can do is set out what we think our the stepping stones between here and there, and keep plugging away at them. Our personal ambition is that at as soon as possible, we individually can be erased out of the picture!

[OpenElectronics] Can you tell us more about the collaboration with Fab Hub and the cooperation with OpenDesk project recently launched, what about the work done at openstructures? Did you meet the founders?

[OpenElectronics] Can you tell us more about the collaboration with Fab Hub and the cooperation with OpenDesk project recently launched, what about the work done at openstructures? Did you meet the founders?

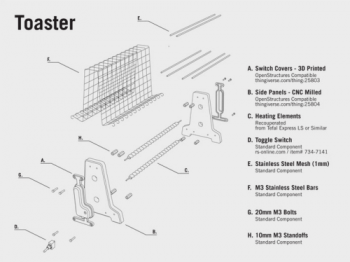

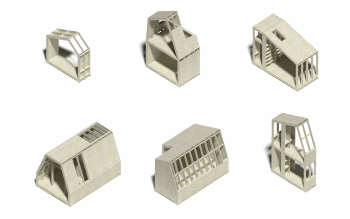

[Alastair Parvin] I have met one of the founders. OpenStructures is an awesome project, which I think will be fully realised by either by the first explosively popular products built using the system, or a big player like IKEA adopting the standard (OpenStructures + IKEAHacks!). Generally speaking (much like the software question), we have sought to adopt existing open standards (for example the 4×8 / 1200x2400mm standard plywood size). But my impression is that all of the open hardware projects are, as a family, slowly edging us towards an emerging new set of standards.

The OpenDesk and Fab Hub projects are sort of parallel, almost spin-out 00 projects to WikiHouse, they came almost from identifying our own problems and saying ‘At some point, the world is going to need a…’ . The question the team are exploring is. Is it possible to build an open commercial platform for distributed designers, makers and users. Obviously furniture is a much more bounded problem than housing, but it allows you to engage with all the pragmatic complexities of standardisation, variance, licensing, micro-economy, digital customisation, quality-control etc, and the interesting spectrum that exists between the person who wants to do everything for themselves, and the person who wants to do some of the work themselves, or the consumer who simply wants to be able to know the provenance of their product, or have customised products. A viable economy based on the many-small, not just the few big and the one-size-fits-all.

[OpenElectronics] What’s the future that we can imagine? My impression is that it’s no more about DIY but more about distributed, fairer, manufacturing and a real Peer to Peer approach, where everyone can create something that might interoperate with others. Am I right?

[Alastair Parvin] I hope so! I think that’s important, to not just see this as a ‘DIY’ amateurs- only thing, but actually, as you say, as the industrial tools for a new kind of economy, one which is open, micro and social. Fundamentally, in the case of housing, that’s about putting different kinds of values in charge of industrial production, and rewriting our current industrial economy of extraction, consumption, resource-intensive production shipping and waste. That’s an exercise in technology, but of course it’s also an exercise in what civic framework comes with that technology (technology always comes with an embedded civic framework!). For example, I imagine we’d like to imagine a form of democracy where open Access to knowledge, tools and certain capabilities is a basic right. That’s not necessarily a utopia, it’s just a different direction of travel based on a different set of processes. But between here and there are innumerable (fascinating) proble ms, such as liability, certification, data privacy, marketisation, material scarcity, trust/ legitimacy, monopoly, any of which makes it much harder to predict where this is going than we generally tend to think!

Pingback: Interview to Alastair Parvin and Wikihouse proj...

Pingback: Is Open Source Hardware for People or for Businesses? | Open Electronics

Pingback: Best Open Hardware Conferences Coming Up in 2014 | Open Electronics

Pingback: L’Open Source Hardware: una questione di Persone o di Business? – Simone Cicero