- How to Adjust X and Y Axis Scale in Arduino Serial Plotter (No Extra Software Needed)Posted 3 months ago

- Elettronici Entusiasti: Inspiring Makers at Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 3 months ago

- makeITcircular 2024 content launched – Part of Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 5 months ago

- Application For Maker Faire Rome 2024: Deadline June 20thPosted 7 months ago

- Building a 3D Digital Clock with ArduinoPosted 12 months ago

- Creating a controller for Minecraft with realistic body movements using ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- Snowflake with ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- Holographic Christmas TreePosted 1 year ago

- Segstick: Build Your Own Self-Balancing Vehicle in Just 2 Days with ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- ZSWatch: An Open-Source Smartwatch Project Based on the Zephyr Operating SystemPosted 1 year ago

How to build an Omni Wheels Robot

The invention of the wheel, literally revolutionized the history of man. Thanks to it, it was possible to create forms of transportation, invent new industrial and architectural machinery. The wheel is so perfect that no one would think to improve it but recently some special, revolutionary wheels have been invented. These wheels are called “omnidirectional” and essentially consist of a set of normal wheels assembled in such a way as to allow new kind of movements.

With omnidirectional wheels is possible to create moving platforms with only three or four wheels, with evident savings respect to the version seen before. However, using wheels of this kind you lose the ability to exploit full motor torque and, in the case of rough surfaces, these are unable to guarantee an exact forward direction and, for this reason, have not been used often on a commercial scale.

Omnidirectional wheels can be used to create simple three wheels platforms and small robots, such as those competing in the RoboCup.

There is a third possibility to create omnidirectional platforms: use recently invented wheels called Swerve Crab Drive. In addition to the classical rotation, these wheels have the possibility to revolve around their diameters. To avoid the motor wires to be intertwined, the traction mechanism is conveyed through gears through the fixing pin. A second mechanism allows the wheel to turn on itself: a total 5 to 8 motors is needed (for four wheels platforms), depending on whether all the wheels can steer or only some of them.

Such a solution implies not negligible costs, however, the freedom of movement that you end up having is quite significant since each wheel rotates according to the direction of the movement. Each wheel is therefore able to transfer all the engine power to the ground. The platform is also insensitive to uneven terrains and you’ve great maneuverability and accuracy.

Our OmniWheels robot

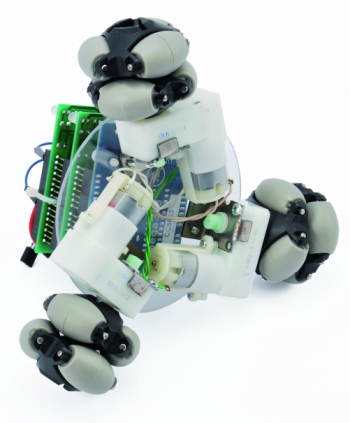

After having studied the functionalities of these type of wheel we ended up creating a small robotic platform using three omniwheels, arranged with a 120° angle between them. The goal was to have a cost-effective, easy to assemble, platform based on Arduino, reusing components coming from other projects.

Omniwheels available on the market are usually very expensive, therefore we preferred to use 48 mm diameter wheels that are available in our store: these are half-wheels because, to achieve a complete omni-directional wheel, you need to assemble two of these wheels with a 60° offset. To achieve our six-wheeled platform we therefore need six of these. For the motors, we used two geared motors, controlled with two motorshields.

We picked the motorshield since it gives us the ability to configure the pins to control the power drivers and, in this way, with two shields, you can control a total of four engines.

Table 1 – Pin assignment to motorshields

| shield | pin | Arduino connection | Motor |

| 1 | PWMA | 3 | A |

| 1 | DIRA | 2 | A |

| 1 | PWMB | 9 | B |

| 1 | DIRB | 8 | B |

| 2 | PWMA | 5 | Not used |

| 2 | DIRA | 4 | Not used |

| 2 | PWMB | 10 | C |

| 2 | DIRB | 12 | C |

It is essential to follow strictly what’s in the Table, because all the three engines must have the same power supply: in our case, a PWM signal at the same frequency.

Table 2 shows the registers and timers used, by the analogWrite function which allows you to set the PWM outputs. The PWM signal headed to pins 5 and 6 uses the Timer0 register but generates a PWM signal with twice the frequency of the other, causing light disparities in the engines operation.

Table 2 – Registers associated with the Arduino PWM.

| pin | function | shield | Timer | register | PWM frequency |

| 3 | PWMA | 1 |

2 |

OC2B |

488,28 |

| 5 | PWMC | 2 |

0 |

OC0B |

976.56 |

| 6 | Not used |

0 |

OC0A |

976.56 | |

| 9 | PWMB | 1 |

1 |

OC1A |

488,28 |

| 10 | PWMD | 2 |

1 |

OC1B |

488,28 |

| 11 | Not used |

2 |

OC2A |

488,28 |

It is vital that the direction of the rotation of the motors is homogeneous: to allow the motors to turn in the same direction, the bit DIRA, DIRB, DIRC of the motors drivers must have the same logic setting. For example, when these bits are set to logic zero wheels shall rotate clockwise.

Wiring is very simple: for the electronics you just need to stack the shield on on top of another on the Arduino, then it is sufficient to wire the engine by connecting the wires to the appropriate terminals of the shield.

Power is supplied by a two cells LiPo battery connected directly to the Arduino power plug, whose voltage, even when the battery is fully charged (over 8V), does not create problems, due to the voltage drop due to the Arduino internal diode and due to power losses on the drivers.

To complete the hardware you need to install an PNA4602/IR38DM IR sensor that will be used as a receiver for a cheap remote control based on infrared technology.

You just need to connect the sensor power to the +5 V and GND pins of the Arduino board and the output must be connected to the 6 digital pin. To filter out possible interference from the motors we soldered a small 100 nF capacitor directly on the power pin of the IR sensor. To attach the wheels to the axis of the motors you need to tinker a little, since the shaft of the geared motors has a smaller diameter than that of the wheels: you need an adapter or a bit of (good) glue.

For the remote control we designed a cheap but very functional solution, which consists in recycling the infrared remote control of a toy helicopter: this solution is ideal as you can get such stuff spending peanuts: it is not easy to fly these helicopters so it is very likely that someone ended up with a spare remote control :)

There are different remote controls on the market, but all share the technology : serial transmission via modulation of infrared rays. Our remote was from a small three channels helicopter (commercial value of 20 Euros).

All we had to do was to discover and reconstruct the codes used to receive the optical signals and convert them into electrical impulses. Doing this, took a very simple 38 kHz PNA4602/IR38DM sensor, that can be easily connected to the Arduino. From the web page https://github.com/adafruit/Raw-IR-decoder-for-Arduino we downloaded the sketch named Raw-IR-decoder-for-Arduino that allows the analysis of the bits coming from any serial transmission, regardless of the speed and the type of bits sent.

After having successfully extrapolated the remote control signals and processed the bit sequence you obtain the values for each channel.

| byte | name | function | Value at rest | Increase if you move the stick to the | Decrease if stick shifted to |

| 0 | yaw | turn |

63 |

left |

right |

| 1 | pitch | foward |

63 |

back |

front |

| 2 | throttle | power |

0 |

front |

back |

| 3 | trim | trimmer |

— |

left |

right |

The protocol used in the IR remote control is as follows:

S 0YYYYYYY 0PPPPPPP CTTTTTTT 0RRRRRRR AND

S – Start Symbol

Y – 7-bit yaw

P – 7-bit pitch

C – 1-bit channel – 0 channel A, 1 channel B

T – 7-bit throttle

R – 7-bit trimmer

E – End Symbol

Variable names refer to the functions carried out by the helicopter, the term YAW indicates the rotation on itself, the term PITCH indicates the advancement and THROTTLE the ascent and descent.

In our application, however, we use the functions in a slightly different way: the right stick consists of two channels and provides indication about the direction and speed of the platform while the trimmer will be used to set the rotation on itself.

Now we just need to write the Arduino firmware which operates the platform, after having understood how to control the omnidirectional wheels. In usual applications operating engines is quite intuitive: being two or four wheels, the operation principle is the very same. Just think of a crawler robot, if the wheels turn in the same direction the robot moves on, if they rotate in opposite directions the robot turns on itself: using omnidirectional wheels all this is not so intuitive, even less if you use a three wheels structure instead of four wheels one. To solve the puzzle you need to work on a bit of math, specifically vectors, and think about how the wheels behave when set into rotation.

Sketch

// OmniWheels

//open-electronics.org

//by Mirco Segatello

#define IRpin 6 // pin for IR sensor

#define SIGNAL_SIZE 32 // number bit of sequence

#define SIGNAL_START 1600 // width bit start

#define SIGNAL_0_min 150 // width bit 0 min

#define SIGNAL_0_max 250 // width bit 0 max

#define SIGNAL_1_min 450 // width bit 1 min

#define SIGNAL_1_max 650 // width bit i max

unsigned int SignalWidth[SIGNAL_SIZE];

byte yaw, pitch, throttle, trim;

#define DIRA_pin 2

#define PWMA_pin 3

#define DIRB_pin 8

#define PWMB_pin 9

#define DIRC_pin 12

#define PWMC_pin 10

#define DIRD_pin 4

#define PWMD_pin 5

float motA, motB, motC;

int PWMA, PWMB, PWMC;

int i;

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(9600);

pinMode(IRpin, INPUT);

pinMode(DIRA_pin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(DIRB_pin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(DIRC_pin, OUTPUT);

analogWrite(PWMA, 0);

analogWrite(PWMB, 0);

analogWrite(PWMC, 0);

Serial.println("Wait IR Signal...");

}

void loop()

{

if(IR_Receive()==0)

{

Serial.print("yaw=");

Serial.print(yaw, DEC);

Serial.print ("\tpitch=");

Serial.print(pitch, DEC);

Serial.print ("\tthrottle=");

Serial.print(throttle, DEC);

Serial.print ("\ttrim=");

Serial.print(trim, DEC);

Serial.println();

SetMotor();

delay(200);

}

}

void SetMotor()

{

motA = 4.0 * (-0.5* float(63-yaw)-0.866*float(63-pitch)) + float(63-trim);

motB = 4.0 * (-0.5* float(63-yaw)+0.866*float(63-pitch)) + float(63-trim);

motC = 4.0 * (float(63-yaw)) + float(63-trim);

PWMA = int(constrain(motA,-255,255));

PWMB = int(constrain(motB,-255,255));

PWMC = int(constrain(motC,-255,255));

Serial.print("PWMA=");

Serial.print(PWMA);

Serial.print("\tPWMB=");

Serial.print(PWMB);

Serial.print("\tPWMC=");

Serial.println(PWMC);

Serial.println();

if (PWMA < 0)

{

analogWrite(PWMA_pin, abs(PWMA));

digitalWrite(DIRA_pin, HIGH);

}

else

{

analogWrite(PWMA_pin, PWMA);

digitalWrite(DIRA_pin, LOW);

}

if (PWMB < 0)

{

analogWrite(PWMB_pin, abs(PWMB));

digitalWrite(DIRB_pin, HIGH);

}

else

{

analogWrite(PWMB_pin, PWMB);

digitalWrite(DIRB_pin, LOW);

}

if (PWMC < 0)

{

analogWrite(PWMC_pin, abs(PWMC));

digitalWrite(DIRC_pin, HIGH);

}

else

{

analogWrite(PWMC_pin, PWMC);

digitalWrite(DIRC_pin, LOW);

}

}

int IR_Receive()

{

int Status=0;

while(pulseIn(IRpin, HIGH) < SIGNAL_START)

{

}

for(i=0; i < SIGNAL_SIZE; i++)

{

SignalWidth[i]=pulseIn(IRpin, HIGH);

}

yaw=0;

pitch=0;

throttle=0;

trim=0;

for( i=1; i < 8; i++)

{

if (SignalWidth[i] > SIGNAL_0_min && SignalWidth[i] < SIGNAL_0_max)

bitClear(yaw, 7-i);

else if (SignalWidth[i] > SIGNAL_1_min && SignalWidth[i] < SIGNAL_1_max)

bitSet(yaw, 7-i);

else

//Serial.print("Error");

Status = -1;

}

for(i=1; i < 8; i++)

{

if (SignalWidth[i+8] > SIGNAL_0_min && SignalWidth[i+8] < SIGNAL_0_max)

bitClear(pitch, 7-i);

else if (SignalWidth[i+8] > SIGNAL_1_min && SignalWidth[i+8] < SIGNAL_1_max)

bitSet(pitch, 7-i);

else

Status = -1;//Serial.print("Error");

}

for(int i=1; i < 8; i++)

{ // il primo bit è sempre zero

if (SignalWidth[i+16] > SIGNAL_0_min && SignalWidth[i+16] < SIGNAL_0_max)

bitClear(throttle , 7-i); //viene trasmesso prima il più significativo

else if (SignalWidth[i+16] > SIGNAL_1_min && SignalWidth[i+16] < SIGNAL_1_max)

bitSet(throttle , 7-i);

else

Status = -1;//Serial.print("Error");

}

for(int i=1; i < 8; i++)

{

if (SignalWidth[i+24 ] > SIGNAL_0_min && SignalWidth[i+24] < SIGNAL_0_max)

bitClear(trim , 7-i);

else if (SignalWidth[i+24] > SIGNAL_1_min && SignalWidth[i+24] < SIGNAL_1_max)

bitSet(trim , 7-i);

else

Status = -1;//Serial.print("Error");

}

// yaw è modificato da trim

int crz = float(yaw)-0.3*float(trim-63);

crz = constrain(crz, 12, 115);

yaw = map(crz, 12, 115, 0, 127);

return Status;

}

Pingback: How to build an Omni Wheels Robot | Heron | Sco...

Pingback: ELECTRICAL

Pingback: Robot Projeleri | CCS C ile Pic Programlama

Pingback: 100+ Robotics Projects for Final Year Engineering Students » The Shastra Phoenixbioinfosys