- How to Adjust X and Y Axis Scale in Arduino Serial Plotter (No Extra Software Needed)Posted 3 months ago

- Elettronici Entusiasti: Inspiring Makers at Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 3 months ago

- makeITcircular 2024 content launched – Part of Maker Faire Rome 2024Posted 5 months ago

- Application For Maker Faire Rome 2024: Deadline June 20thPosted 7 months ago

- Building a 3D Digital Clock with ArduinoPosted 12 months ago

- Creating a controller for Minecraft with realistic body movements using ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- Snowflake with ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- Holographic Christmas TreePosted 1 year ago

- Segstick: Build Your Own Self-Balancing Vehicle in Just 2 Days with ArduinoPosted 1 year ago

- ZSWatch: An Open-Source Smartwatch Project Based on the Zephyr Operating SystemPosted 1 year ago

Rome crowns Massimo Emperor of Makers

I should have written this report on Monday last but I was so tired after four days in Rome at the Maker Faire, and with so many things to talk about, that I decided to have a few days off. Which was a stroke of luck because some of questions I wanted to ask the key exhibitors in Rome (absolutely impossible at the time for the heaving masses), I had time to put to Massimo Banzi when I bumped into him yesterday on the flight from Milan to Hong Kong. I was going to the usual Hong Kong Electronics Fair and he was off to the Shanghai Maker Carnival.

Rome Maker Faire, a runaway success

I’m sure many of you have already read the event’s closing press release, with all the relevant figures: almost 35,000 attendees over the four days; 1,500 people at the Thursday conference; 6,000 students packing Palazzo dei Congressi in the EUR district on Friday; over 25,000 visitors on Saturday and Sunday.

Beyond these numbers, which are significant, of course, the success of the event so heavily promoted by Massimo Banzi and Riccardo Luna was mainly due to the sheer quality of the showcased products, which in many ways surpassed the original American event. It was no coincidence that we saw Dale Dougherty, creator of Maker Faire and founder of Make, listening carefully to all the speeches and wandering around maker stands looking for new ideas and inspiration.

If you were at this first European Maker Fair, you’ll certainly have enjoyed the opening conference, with its fascinating presentations, videos and demos dedicated to Inspiring the Future.

Once you’ve seen a 15-year-old boy preparing a test for beating pancreatic cancer, how can you fail to be inspired to try and do something like that yourself? Or be blown away by the story of Alice Taylor, who teaches children to use new technologies to build the toy of their dreams, a toy unique and totally different from any other?

And let’s not forget Nina Tandon, making spare parts for the human body by integrating a bioreactor with technology borrowed from 3D printing.

So absolutely Inspiring the Future, with a single theme: improve our world, one step at a time, as writer David Gauntlett says, sharing knowledge and experience. A grass-roots movement that will gradually rise as far as the world’s decision-makers. Or so we hope.

Anyone who followed the conference all the way through will already have the distinct feeling that today’s current technology is more than able to make radical changes to our society, defeating ignorance, unemployment and poverty. How to reMake the World was the title of the conference and its objective, seen clearly in many examples in Rome.

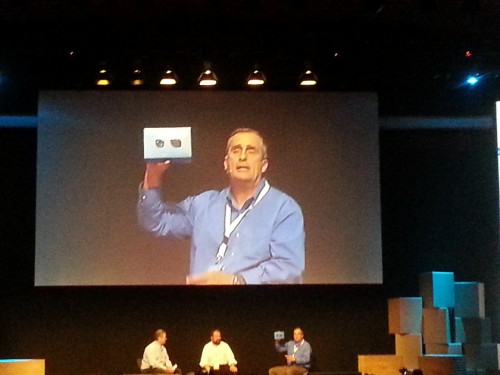

Riccardo Luna was a truly engaged moderator for the conference but Massimo Banzi was the real star performer. He surprised everyone (not a word was leaked in advance) with the Galileo board, a project targeting both the world of education and that of makers, the result of a partnership with Intel, signed just two months before. In this short time span Arduino and Intel managed to create an embedded board combining the world of Arduino with the power of a GNU/Linux-based operating system. Of course, the processor chosen uses CISC architecture with consumption three times higher than ARM processors, as many have pointed out. For their part, the people involved simply reply that this is just the first in a series of boards that will come out of the Arduino-Intel cooperation. To emphasize the importance of this agreement, the preview of the Galileo board was attended by Brian Krzanich, CEO of Intel, a company that was also a sponsor of the Rome Maker Faire, present at the event with a big stand.

One thousand of the new Galileo boards were distributed free of charge to attendees and another 50,000 will be donated to universities around the world. The massive participation of a giant like Intel, not to mention the presence of Brian Krzanich, had some of us wondering if Massimo Banzi was about to follow in the footsteps of Bre Pettis, founder of MakerBot Industries, who recently moved lock, stock and barrel to the multinational Stratasys for six hundred million dollars, actually reneging part of his open-source philosophy.

“Are you kidding?” says Massimo. “Arduino is a far more complex and articulated reality, with operations in many countries worldwide. The key aspect of the agreement with Intel (which we’re particularly proud of) is being able to get one of the world’s leaders to produce a completely open-source board in both hardware and software, with full documentation. This will be a huge help to thousands of students for learning electronics, computer science and robotics. We’re even donating 50,000 items.”

Massimo adds “I also wanted to respond to the people who’ve recently criticized the fact that Galileo and other new boards (Yún and Arduino TRE) are produced in the United States or Taiwan. The truth is that our project has been characterized from the start by its international platform. I’m Italian but I’ve been living and teaching in Switzerland for years; David (Cuartielles) is Spanish but lives in Malmö; David Mellis works and teaches in the United States … we work with a great many companies, scattered half way round the world, so it’s standard practice that some boards are made in Italy, others in the States, and so on and so forth.”

It goes without saying that we got our hands on a couple of Galileo boards while we were in Rome, so catch the next issue of Elettronica In to find out more: Marco is at hard at work for you. For more information on the technical features of this board, take a look at the post of a few days back. As for availability, Galileo will be on sale from the end of November at a retail price of 40–50 US dollars.

Speaking of prices, something should change in the Arduino Yún selling price according to Massimo: “The current price is the result of quite a small first batch of production but now, with much larger runs, we hope to be able to push the retail price down a bit.”

In addition to the preview presentation of Galileo, the Maker Faire was the occasion for the new Arduino TRE board to be announced, available in spring 2014 and produced in partnership by the BeagleBoard foundation and Texas Instruments. This is another board combining a section of an Arduino-based interface with the physical world and a processing and connection section that uses a Sitara processor by Texas Instruments running GNU/Linux. At the moment that’s all we know about this board, gleaned from the scant official press release (… also because the board is still being developed).

No other past Maker Faire could boast as many important announcements as we had here in Rome, neither New York nor San Mateo, the two most important American events.

In short, a real triumph for Massimo Banzi, acknowledged by all as the star figure at this show.

However, the real test for the Rome Maker Faire was yet to come. What would the public think? The wait was tense because the financial commitment for organizing the event had been quite significant and failure would have meant the future of the initiative being nipped in the bud.

Personally, I remember how worried the managers at Asset-Camera were when I met them before the summer, concerned about not being able to attract just a few thousand makers to the event, and in stark contrast with my huge optimism, based on my knowledge of the history of the American Maker Faires and the quality of the event that was being organized. My curiosity, if I had any, was to understand whether the structure would withstand the crush of the crowds I was sure would hit Rome.

I was right, as it happens, especially for the Saturday, when the police actually had to intervene to control the flow of visitors, many of whom couldn’t get in and had to put their visit off to Sunday.

In any case, after Thursday’s conference, a wave of optimism swept through Friday (dedicated to schools), marked by an literal invasion of nearly 6,000 students, the first to see the projects of more than 200 makers from all over Europe who had set up their stands on Thursday. The students were also the first to bring to life the various laboratories and workshops.

The Weekend

Despite a heavy storm that hit Rome on Saturday morning, only a few hours after it opened it was virtually impossible to move down the aisles of the Maker Faire and around the display areas: everyone wanted to see, touch and understand how the exhibits worked. Many young people and lots of families with children, but also plenty of folk from the rest of Europe were to be seen. A success also from this viewpoint, a real European Maker Faire and not just an Italian event. Then with English as the official language, of course, since more than half of the exhibitors came from abroad. What better proof than in the field, over and above all the rhetoric, that you need to speak at least English to be partakers of the new digital era.

Even the Arduino Store (something similar to the American Maker Shed), the space where visitors could buy products, was mobbed, with long queues for the checkout.

Not to mention our own booth, which I practically couldn’t get a photo of because of the wall of people in my way. Boris and Alessandro didn’t even manage to grab a sandwich until late afternoon …

In a nutshell, it was a success on all fronts, which rewarded those who believed in this project.

Paradoxically, in my opinion, it was too much of a success and the number of events made it impossible to enjoy this great initiative to the full. Despite spending four days in Rome, I wasn’t able to contact many of the makers present and participate in all the scheduled events. EUR’s Palazzo dei Congressi revealed its limits, certainly not for a lack of organization but for the sheer mass of visitors.

Massimo Banzi doesn’t agree. “Sure, our most optimistic forecasts predicted 20,000 visitors, a number compatible with the facilities. In reality, the numbers that entered the gates over the weekend were beyond belief. I understand there were even problems at the coffee bar, which ran out of sandwiches and drinks. Next year we’ll try to make better use of the space available and optimize the current structure, which has other facilities we could exploit. Also because we don’t want to stop here and the number of visitors absolutely has to grow. At the first Maker Faire in New York there were 35,000 visitors, the number we had in Rome, while the second year clocked up 50,000: we don’t want to be outdone. But there’s another reason why we want to stay in Rome. We don’t intend to change anything because we worked well with Asset-Camera and they believed in this project completely, not only taking a big financial risk but also with a number of people sticking their necks out and putting their jobs on the line if it had flopped. We’re not considering a change of venue for the foreseeable future.”

Another criticism heard about the Rome Maker Faire was that it was too Arduino-oriented and a few stressed the absence of some important players in this new wave of innovators, first of all the Raspberry Pi foundation and its board, of which nearly two million units have been sold to date … “The organizers placed no vetoes and didn’t stop anyone taking part,” Banzi says. “If the Raspberry Pi Foundation wanted to be present, as a maker, it simply could have replied to the Call and it would certainly have been accepted, and if it wanted to participate as a sponsor, it should have followed the same procedure as everyone else, contributing financially or providing something meaningful and relevant to the event. Probably, like many other major corporations, they didn’t believe in this project and kept a low profile.”

We’re about to land so just one last question. “Apart from countless accolades and the runaway success of this event, what was the biggest buzz you got from this first Maker Faire?”

“Certainly the presence of many families with children who dragged their parents from stand to stand was in perfect harmony with the spirit of a Maker Faire. On the other hand, everything we do today, we do it for them.”